We asked Larry List, who has curated "The Imagery of Chess Revisited," "32 Pieces: The Art of Chess," and, most recently, "Highlights of the George & Vivian Dean Chess Collection," to tell us more about the miniatures representing the legend of the introduction of chess to Persia.

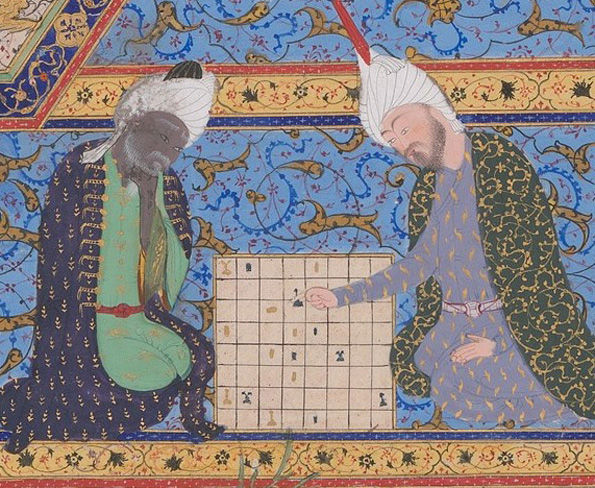

Three representations of "Buzurjmihr Masters the Game of Chess" are housed in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum. That the story was illustrated in the Shahnama (Book of Kings), recounting the tales of ancient heroes and rulers of pre-Islamic Iran, indicates that the tenth-century poet Abu'l Qasim Firdausi regarded this story as significant as a scene of battle or diplomacy. Indeed, it was both. It was also a turning point in the history of chess. Of the hundreds of board games devised in India, chess was the one that made its way to Persia. The Indian rajah Dewarsah sent it as a riddle and challenge to the Persian shah Khusrau. If the shah could not figure out what this strange ornate board and pieces signified and how they were used, the rajah would pay no more tribute. In each illumination, the shah's wise man, Buzurjmihr (also transcribed as Buzurgmihr), is shown solving the riddle of how the chess pieces were arrayed on the board and how the game was played.

It is not easy to make out the distinct forms of the tiny pieces in the illuminations. They are consistently shown on an 8 x 8 board. (The board has not been checkered as we expect today.) In the two miniatures dated to the fourteenth century, the pieces are red and black, while in the splendid image from the time of Shah Tahmasp (1524–76), the pieces are gold and black (perhaps oxidized silver).

Images, from top: Detail from "Buzurgmihr Masters the Game of Chess", Folio from a Shahnama (Book of Kings), ca. 1300–30. Abu'l Qasim Firdausi (935–1020). Iran or Iraq. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1934 (34.24.1); Detail from "Buzurjmihr Masters the Game of Chess", Folio from a Shahnama (Book of Kings), ca. 1330–40. Abu'l Qasim Firdausi (935–1020). Iran, probably Isfahan. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Monroe C. Gutman, 1974 (1974.290.39); Detail from "Buzurjmihr Masters the Game of Chess", Folio from the Shahnama (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp, ca. 1530–35. Abu'l Qasim Firdausi (935–1020). Painter (attributed to): 'Abd al-Vahhab. Iran, Tabriz. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Arthur A. Houghton Jr., 1970 (1970.301.71)

In each instance, the artist has made his own choices, independent of Firdausi's text, which describes the pieces as teak and ivory in one version, and, in another version, as ebony and ivory. The artists, who most likely did not play chess, did a fair— but not perfect—job of depicting recognizable shapes and placing pieces on plausible squares, according to early Muslim chess rules. If truly illustrating the story, the artists would have drawn the pieces using ornate, representational Indian designs. In fact, the pieces, as best they can be seen, resemble those of the chess set from Nishapur, Iran, even though they were painted two to four centuries later, respectively.

Chess set, 12th century. Iran, Nishapur. Stonepaste; molded and glazed. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Pfeiffer Fund, 1971 (1971.193a–ff)

Serendipitously, the circa 1300–30 version portrays a game "opening," the circa 1330–40 version shows a "mid-game" position, and the circa 1530–35 version shows the transition to an "end game." In each case, the Indian emissary is moving his Firzan, which, in western Europe became the Queen.

Once it became popular in Persia, chess was then taken along as an entertainment by Islamic warriors as they moved across North Africa and into Spain, whence the game spread throughout Europe. Thanks to Buzurjmihr, the entire world has chess as a game in common, and all because of a ruler's riddle!